Blowing up some portion of Syria’s chemical weapons infrastructure changes everything. Or nothing, depending on who you ask.

Don’t ask me.

All I know is that we’re walking into whatever was planned for us.

If Bashar al-Assad actually launched a chemical weapons attack, it must’ve been to solidify his Russian support by escalating tensions with the West.

If someone else launched a false chemical weapons attack, it must’ve been to goad the West into action in Syria.

Either way, we’re nice and predictable. So whoever did launch the attack is doing well.

But let’s turn to financial markets. The global economy continues to slow. And not when it’s supposed to.

We’ve looked into the US yield curve a few times now. The yield gap between American short and long duration bonds just reached the lowest level since 2007. Any lower and it signals a coming recession.

Part of the curve is inverted if you look at bets on interest rate policy in the forwards market. But only a few years into the future. This basically means speculators are anticipating an interest rate cut in about two years’ time. It’s the first time in 13 years that this has happened, taking us back to 2005.

Despite those two ominous dates, there isn’t much concern over any of this. Perhaps because the bond market is so manipulated by central banks. Without a free market setting yields, it may be giving a misleading signal. So don’t worry about it too much, the media reassures me.

The problem is, it might be misleading to the upside. An unmanipulated yield curve could be signalling a recession clearly. Remember, when quantitative easing (QE) was launched, monetary policy makers said it would push up bond prices and interest rates would go down. The precise opposite happened in the aftermath of each intervention. So it’s not like these people know what they’re doing.

There are two explanations for what happened each time QE was implemented. Perhaps this is a case of “buy the rumour, sell the news”. QE did have the intended effect, just in anticipation of the policy announcement. But the time it was actually announced, it was old news. There’s a German saying that anticipation is better than gratification.

The alternative explanation is that investors saw QE as inflationary and backed away from bonds each time QE was announced.

Either way, it’s clear that QE is messing with a yield curve that grows closer to signalling a US recession by the month. You’d think they’d manipulate it to signal otherwise.

Earnings season in the US began last week, so we’ll be looking for more hints from company financial statements. So far, CNBC called the results “ominous”.

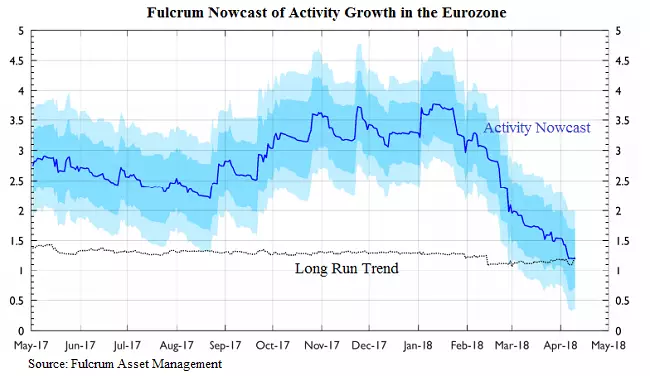

Over in Europe, a few months of surprising growth are coming to a concerning end. The Financial Times reports how the fund manager Fulcrum Asset Management is concerned about the sudden change. Economic activity has tumbled since February.

The details were provided in another FT article:

A wide-ranging measure of eurozone industry unexpectedly fell in February, echoing surveys of businesses that suggest the bloc’s economic growth may have eased in the first quarter.

Industrial production fell 0.8 per cent in February from January, marking the third straight monthly decline for the gauge. Economists had forecast a 0.1 per cent uptick, according to a Reuters survey. Falls were the most pronounced in capital and durable goods. The former fell 3.6 per cent, while the latter declined 2.1 per cent.

Energy was a bright spot, up 6.8 per cent. Data from individual countries released previously suggested cold weather may have provided a boon to the energy sector.

Industrial production was still up 2.9 per cent from February 2017, but the rate of growth slowed sharply from 3.7 per cent in January and 5.2 per cent in the final month of 2017.

Citigroup’s Global Economic Surprise Index has turned negative and Reuters reports “Euro zone businesses rounded off the first quarter of 2018 with their slowest growth in over a year – and much weaker than expected – as new business took another hit from a stubbornly strong euro, a survey showed.”

More concerning than the backward-looking indicators of the economy is the forward-looking stockmarket. If the February tumble in stocks around the world was a warning shot about economic change, we’re in for a sharp contraction. Perhaps the market knows something we don’t.

The real question in all this is who is the weakest link. An economic slowdown is likely to bring about some sort of crisis. Probably a debt crisis. But where?

Could it be the UK?

According to Australia’s Business Insider, the UK was the only major economy where economic growth slowed last year. We’re weak going into this year. Still, the pound is up over 6% since September 2017 against the euro.

Of course, the UK still grew faster than Italy. But that’s the odd thing about the eurozone. It’s a bundle of economies bunched together, so the economic statistics look a lot steadier overall. But when it comes to debts, the eurozone isn’t unified yet. It’s the divergence between the two that’s the worry. More on that in a second.

If the story with Russia continues to escalate, could that be enough to cause trouble for the UK’s economy at a fragile time? It’s well known that the Germans are reliant on Russian gas, so they haven’t been joining in on the bullying effort.

There happens to be a rather enormous opportunity to hedge against Russian- dominated energy markets. It involves a lot of hot air under Devon, if you know what I mean.

Back to QE

An economic slowdown now would reignite old debates about monetary policy.

Interest rates can’t exactly be cut much around the world. The evidence for negative interest rates at central banks spurring growth is iffy.

Fiscal policy is just as shaky. Debts and deficits have recovered about as much as central bank policy.

That only leaves one button for policy makers to push if the economy turns down properly: “PRINT”.

If QE is the only major policy left, it’ll be the policy used.

The thing is, there’s one central bank in the world with legal restraints on its QE. It just happens to be the one ruling over the eurozone.

One currency, one monetary policy, but no shared debts, and a limit to QE policies.

Do you see the problem? I’ll lay it out.

The eurozone’s currency and monetary policy exacerbate economic divergence between eurozone members by ensuring the exchange rate and interest rate applied is never the correct one for a particular nation. The ability for eurozone members to borrow, go broke and default independently makes this distinctly possible in the face of an interest rate and an exchange rate that aren’t helping. And any rescue attempt is hampered by European Central Bank rules.

What could possibly go wrong? We’ll see.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Related Articles:

- The investment power of politically incorrect

- The prospects of the US dollar

- The implausibility of a crash

Category: Economics