Across the world in East Asia, the number 4 holds a grim meaning. Across the many different languages in the region, the pronunciation of the number is very similar to the pronunciation of the word for “death”.

The number is considered grievously unlucky for this connection, and leads to all sorts of interesting anomalies within the countries.

There is often no button in an elevator to access the 4th floor – the buttons available just go from 3 to 5. The 4th floor is not hidden away or barred from access, it has simply been labelled with a number 5.

Some larger apartment complexes go a step further, removing every floor beginning with a 4. Go up one level from the 39th floor… and you’ll find yourself on the 50th.

If you’re looking to buy property there, properties with an address containing a 4 can often trade at a deep discount to their peers. However, many streets don’t have a number 4 at all.

Numbers containing 4s (14, 44, 74 etc) are thought to be as unlucky, if not more so. 14 for example, sounds similar to “want to die” in Mandarin, and is avoided as much as 4.

A gentleman from Singapore (where Mandarin is second only to English) said he wanted to die on the internet earlier this week, due to an investment he’d made. Ironically, he had lost millions overnight in an investment labelled “14” – it was almost like he was just mispronouncing its name.

Thankfully, he is still alive. But the same cannot be said for his investment, and the strategy he used, which had made him millions from a starting pot of only around £25,000.

What went wrong?

Volatility vigilantes

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

– The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway

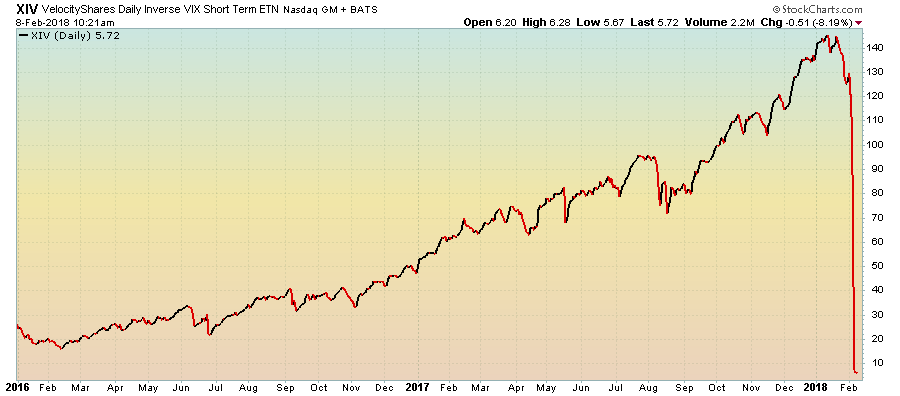

Take a look at this chart.

Beautiful, isn’t it? It’s what the gentleman from Singapore was investing in. Its ticker is not simply “14”, but the roman numerals for 14: XIV.

I admit I am making a small jump here. The ticker for the investment was not the numbers 1 and 4, but the roman numerals for 14: XIV.

What did XIV do? It bet that investors in the US stockmarket wouldn’t expect volatility. As you can see, it was right an awful lot of the time. And then as the day drew to a close on Monday, it suddenly wasn’t.

All the investors who owned a stake in XIV, including the gentleman from Singapore, were brutalised by the long red tail on the right of the chart, and they were left holding less than a tenth of what they had overnight.

The reason the strategy was so successful until now is ultimately thanks to central bank money printing and their enforcement of interest rates that have never been lower in 5,000 years.

More cash in the system has inflated stock prices. This by itself reduces volatility, as volatility and stockmarkets are negatively correlated. When stockmarkets go up, volatility generally goes down. It’s quite rare for both to rise or fall in tandem. This is because stockmarkets take the stairs up, slowly but surely “climbing the wall of worry” to their highs, before taking the elevator down much faster in bear markets.

Volatility has been kept low by stock buybacks. This is when companies borrow money at low interest rates to buy back their own stock. Why would they do this? Well, some companies incentivise their executives to grow the business by paying them bonuses based on earnings per share, or EPS.

While traditionally executives earned this bonus by actually growing the earnings of the business as a whole, with interest rates so low you don’t need to bother with that. Now they can just borrow a load of money, and buy their shares back from the market. By reducing the number of shares in circulation, EPS goes up even though earnings haven’t changed, or even if earnings have decreased.

In the past, temporary dips in the market have been used as an excuse for companies to buy back their stock, which has driven the price back up again. But as we highlighted in December, these corporate stock buybacks have dropped off. And central banks are now talking about raising rates and tapering their money printing programmes.

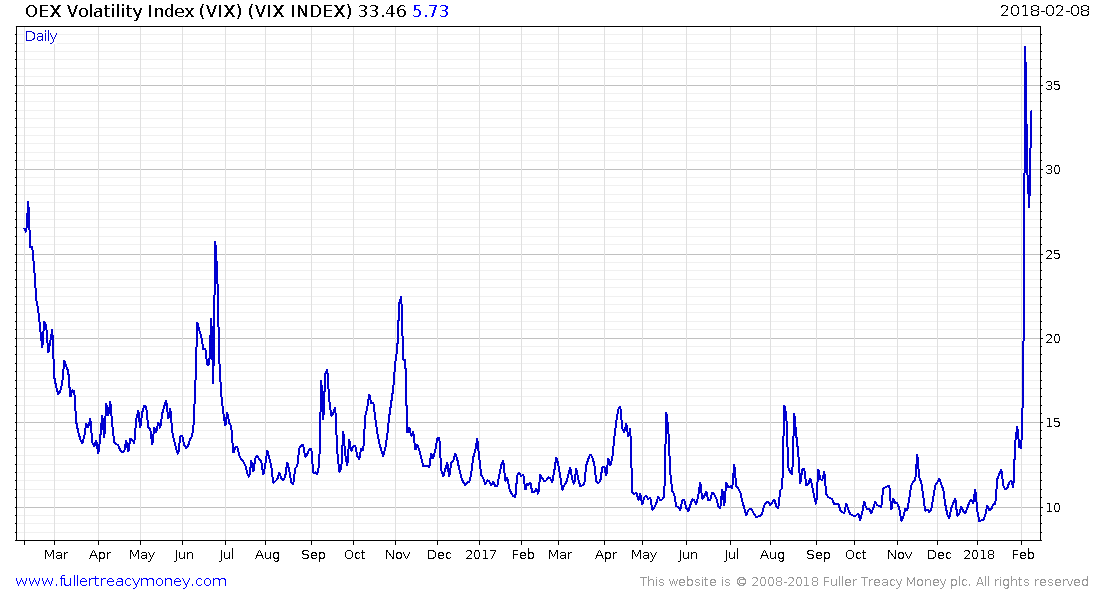

The wobble in stockmarkets last week caused a small spike in volatility, which turned into a firestorm.

Volmageddon

The XIV is an exchange-traded product (ETP) run by Credit Suisse. It is not actively managed, as all it was meant to do was inversely track the VIX, making money when the VIX went down, and losing money when it rose. It’s important to note that the VIX is not actual volatility in the stockmarket – it is a reflection of how much it costs to hedge future risks on the stockmarket.

It is impossible to actually “buy” the VIX. The VIX simply reveals the cost of insurance on the stockmarket, but this is seen as a proxy for actual volatility.

The way ETPs track it is where the fun begins, and is what spelled doom for the XIV.

VIX trackers use VIX futures to track the VIX, which were launched in 2004, long after the VIX was created as an index. As with other futures contracts on indices, two parties agree to exchange money at a certain date in the future. How much either will pay the other depends on the change of the index between the beginning and the end of the contract.

The XIV ETP generated returns for its investors by selling VIX futures – making money for every point or “tick” the VIX went down.

Taking the “short” side on VIX futures like this became more and more popular. Even supermarket managers got in on the game, becoming millionaires in the process.

Among the newcomers were people who would go broke if the VIX went up by much. These “weak hands” had just kept watching the VIX go down and expected the recent past would continue to repeat into the future.

And so when the VIX went up by a little when the American stockmarket dipped last week, they suddenly needed to cover their liability – they bought futures to cancel out or “novate” their position.

This scramble to buy VIX futures forced the price of the futures up, causing more of those who were short to cover their position, creating a feedback loop of people who were short the futures to go long and bid the price up even more – the classic “short squeeze”.

The XIV ETP’s mandate was to inversely mimic the VIX. The only way they were doing this was by being short VIX futures, which moved much more dramatically than the VIX itself. The value of the ETP was eviscerated, as was the Singaporean man’s savings.

Who would have thought that investing in a derivative built of derivatives, which derive their value from an index reflecting the price of derivatives, was a bad idea?

Perhaps it all would’ve turned out right if they’d just called it something other than 14…

Until next time,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Southbank Investment Research

Related Articles:

Category: Economics