Today bitcoin and the financial sector combined their superpowers. Will it be for good or evil?

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) launched bitcoin futures overnight. The immediate result was a bitcoin futures price of $20,000 for February, far higher than the spot price at the time.

That’s effectively a forecast for the bitcoin price coming from people putting their money where their mouth is by betting on it.

If you’re getting déjà vu, it’s because last week the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) launched bitcoin futures too. But that exchange is far smaller and so the CME is considered the main event. It opens the bitcoin futures world to the bigger players.

The question is, what do bitcoin futures mean? What will they do to the price of bitcoin itself in the longer term?

I’m not even sure why the world needs bitcoin futures in the first place, to be honest. The whole point of futures trading was to allow people to hedge and speculate on the price of something without having to get involved in the underlying asset. Messing about with oil futures is far more convenient than shuffling barrels of oil around.

But bitcoin is too similar to a financial asset already to need futures trading. Whether people log on to their bitcoin exchange or the CME should make only a minor difference.

Perhaps the answer is liquidity. The futures market could offer a way for big investors to punt without affecting bitcoin prices directly. That in turn offers a huge opportunity for price manipulation for people active in both markets. Bitcoin investors can look forward to suspicious moves in the price.

The idea that bitcoin futures will push up bitcoin prices is a bit misleading. For a futures contract to come into being, it needs a balance of buyers and sellers. The intermediary might make up a small difference between the two. But in the end, the supply and demand for a futures contract must be quite close. So the influx of futures traders needn’t push up the price of bitcoin.

Perhaps it’s the ability to bet on a falling bitcoin price that makes futures popular. The doubters can finally place their bets too now.

You’d think the exchanges themselves would explain exactly why they’re offering bitcoin futures. But all they seem to know is that people want them.

In such situations I always look to the government for answers. How has the government messed things up badly enough to make a strange thing happen?

In this case, it’s likely that certain investment funds aren’t allowed to invest in bitcoin, but can buy futures on the CME. A pension fund manager, for example, probably can’t buy bitcoin for his funds because of the government restrictions on what he can buy. But he can buy bitcoin futures on the CME.

Under this logic, an utterly terrifying amount of money could be about to flow into bitcoin trading via the futures market. Movements in the futures market could overwhelm bitcoin itself.

But it’s not just the financial sector that’s invading the crypto space. Governments are too. The EU has finalised its crypto crackdown. Individual countries will legislate the agreed rules into law over the next 18 months. Hopefully Britain escapes in time…

The good news for all you rebels out there is that cryptocurrencies can pop up too fast for governments to get a hold of. Even if it isn’t bitcoin that makes the black market function efficiently, it’ll be a different cryptocurrency.

But that probably doesn’t help investors much. Contravening the law for the sake of investment returns is a pretty bad proposition.There’s a far better way to make money from the whole cryptocurrency boom these days anyway.

The remaining housing bubbles are popping

If you go anywhere near the world’s remaining housing bubbles you’ll hear a faint hissing noise.

Sweden is hissing the loudest. House prices are down year on year for the first time since 2012. They’ve fallen between 4% and 6% in just two months, depending on the index you choose. Stockholm apartment prices specifically are falling at a rate last seen in 2008. The majority of Swedes now expect house prices to continue falling.

Last month the Swedish central bank claimed the slowdown in prices was good for stability. That one could go down well in the history books.

In Canada, house prices started falling three months ago. The rate of decline is the highest outside of a recession, but still very small.

In Australia, Sydney house prices fell last month. Auction clearance rates plunged from 80% to 50% this calendar year. Melbourne’s auction rates are close behind, but house prices are flat. In the rest of the country’s capital cities, they’re still rising slowly.

House prices in New Zealand are still on the up too. But sales volume tumbled 16.5% in the key city of Auckland last month.

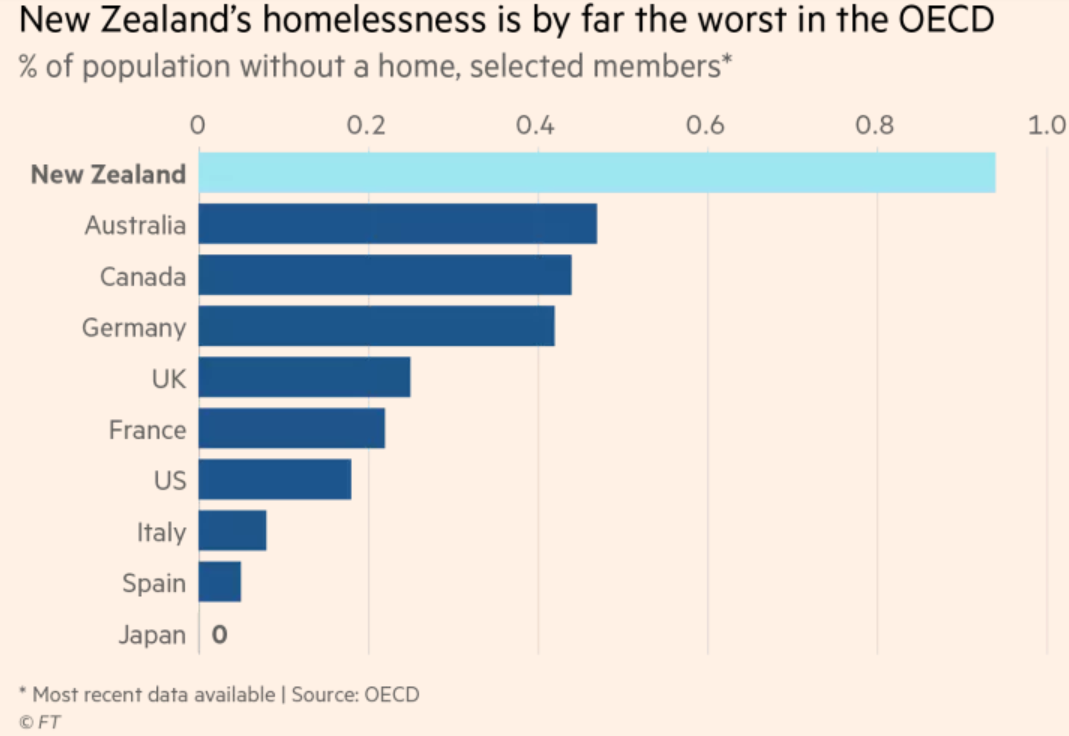

In New Zealand they have a surprising problem due to the housing bubble – extraordinary levels of homelessness. This chart from the Financial Times is a real eye-opener:

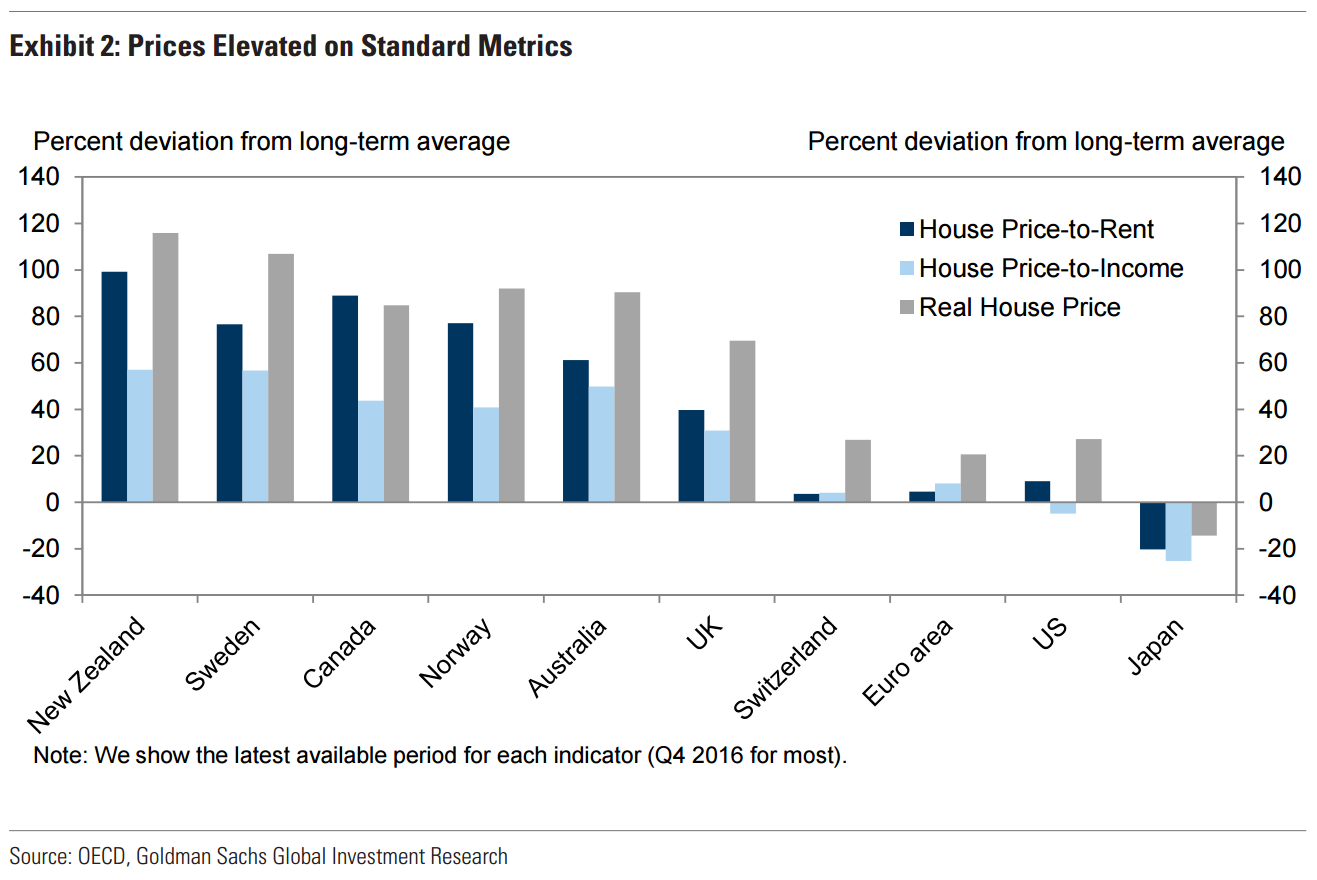

The correlation between housing bubble and homelessness seems very strong. The blog MacroBusiness highlighted a chart from Goldman Sachs which puts together three valuation measures for the markets above:

The two charts together show you that countries with bubbles have homelessness problems. They also suggest the solution to homelessness is painfully obvious: allow a lot more housing to be built. That’ll solve affordability and homelessness together.

It’ll also mean a house price crash…

So let’s get back to what’s actually going to happen.

I don’t know much about the housing bubble in Canada, New Zealand or Sweden. But I know plenty about Australia’s. In fact, I’ve done in-depth research on Australian lending for a PhD.

The key to Australia’s housing bubble is similar to that of the US. The level of debt means people need prices to continue rising. A flatlining housing market is not sustainable for too many borrowers already locked into the asset. They’re relying on house price growth to come good.

Those marginal borrowers will begin to sell once the gains disappear. And then it’s a mad rush to the exit. Perhaps the stalling housing market will trigger Australia’s own sub-prime crisis.

“Solving” the housing bubbles

Countries with housing bubbles are following similar policy paths to deal with the problem. They restrict foreigners from buying existing homes, crack down on lending and provide tax incentives for locals.

Why they don’t just increase the supply of houses significantly is no mystery. Spain and Ireland’s ghost estates are famous. As are the results for the rest of the housing market.

Still, it’s zoning laws that prevent building. Restricted supply is investment demand’s favourite enticement. That’s why people pile into housing to the point of unaffordability. Instead of freeing up supply to fix the problem, governments try everything else they can think of.

Their misguided measures lead to some funny outcomes. There’s an entire industry in Australia for helping foreign Chinese buyers to buy property.

The restriction on bank lending is also evaded. Hedge funds just entered the market to make up the difference. One of Australia’s largest property websites Domain.com.au reported on the not so surprising phenomenon:

Australia’s push to control a housing bubble by reining in bank lending to property developers has unleashed a highly profitable market for shadow lenders, including international hedge funds.

The lenders are funding some developers at more than double the interest rate for the same type of loans that banks were providing just a few months earlier, a reflection of how some construction firms have been forced outside the regular banking system to secure financing.

“Effectively, the risk hasn’t changed, but the pricing today is about 12 per cent, not the 6 per cent that banks were charging 12 months ago – so you are getting very attractive spreads of almost double in this space,” said Martin Scott, the Australian head of the Swiss-based Partners Group, an investment manager with some $US65 billion in assets.

The private sector is a wonderful thing. It doesn’t particularly care about the government’s law. It only cares about meeting demand when and where it’s an efficient allocation of resources. Profit signals that it is.

Regulation and criminalisation just becomes a cost and risk factor that go into the calculation. From drugs to property development, capitalism finds a way.

The real worry is that the combined housing bubbles still left around the world could trigger another financial crisis. Australia and New Zealand’s banking systems rely on foreign funding. Not long ago, Australia’s biggest four banks were valued at more than the entire eurozone’s.

Problems Down Under are big enough to spread fast.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: Economics