Warren Buffett’s annual shareholder letter is out. His disciples around the world are fawning away over the legendary investor’s latest thoughts. But this year’s pontifications are a bit suspect. As you’ll discover below, you’d be better off spending your time with this than reading Buffett’s letter.

I’ve never read one of Buffett’s letters before. I did read an old 1973 version of the Intelligent Investor in which Mr Buffett wrote the preface. Intelligent Investor is the Bible of value investors. And Buffett is known as the Oracle of Omaha for preaching its virtues.

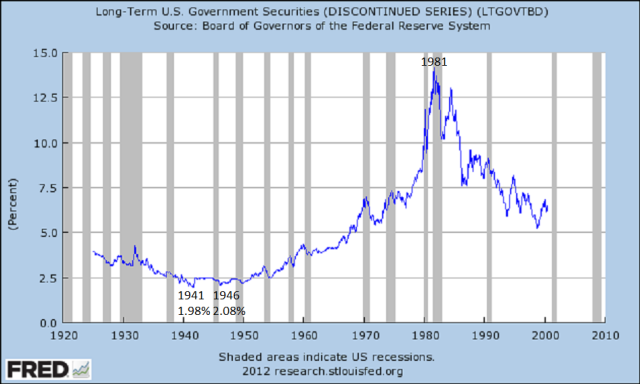

In the 1973 edition, Buffett advised readers to buy bonds because stocks were overvalued. As you might remember, this was just before the epic bear market in bonds took place over the next few years. Inflation rorted bondholders and interest rates lit a fire under monthly mortgage bills.

It’s the perfect lesson why value investing is only a third of the investing equation. Stocks were not expensive, as Buffett thought. They were correctly pricing in the inflation of the 70s. Bond investors were in trouble as interest rates surged.

To make investing work, you should follow the sort of advice which you’ll find in Intelligent Investor. But you can’t ignore economics. And some would argue that looking at charts with technical analysis is important for timing your buys and sells.

Southbank Investment Research has you covered for all three styles in our newsletters. But there’s a fourth take on things. One which the Dividend Letter editor Stephen Bland and I have in common. It’s about a simple reality which most investors ignore. They become gamblers instead of business owners. And they miss out on the proper gains the stock market is designed to provide.

Funnily enough, Buffett uses Bland’s strategy too. But he doesn’t preach it. Or provide his own shareholders with the same privilege…

What Buffett got wrong

Just like in 1973, the value of Buffett’s advice in this year’s shareholder letter is dubious. He says we should all stick to index investing. The idea is to buy a basket of stocks that reflect the stock market index as a whole. Because stock markets go up in the long run, diversifying in this way means you’re best positioned to make money.

The big difference is the lack of investment fees if you use this strategy. There aren’t any investment managers pretending to be geniuses and charging you money for the privilege of investing with them. Over time, those fees add up to a ruinous amount.

But there are a bundle of holes in Buffett’s argument. To be fair, he’s just passing it on from other researchers. But Buffett’s status means millions follow his advice. So what’s wrong with it?

For one, I don’t think “stock markets go up in the long run” is some sort of universal law that always holds. Yes, it has been true in the past. But there must be a reason why stocks have been going up as a group since they were invented. You can’t say they’ll keep going up, unless you understand that reason. What if that reason were about to reverse for the first time ever?

You’ll hear plenty more about this in coming Capital & Conflicts letters. For today, let’s stick with some more basic flaws in Buffett’s advice.

You can’t actually invest in an index

You can buy stocks which are in the index. The distinction is where index investing comes up short. If you take a closer look at what’s actually in a stock market index itself, you’ll see why.

Indices are made up of companies based on a variety of criteria. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, for example, focuses on big industrial stocks. The NASDAQ index has tech stocks because the entire exchange is tech stock focused. Then there’s the S&P500 which has the biggest stocks by market capitalisation (value) along with some other criteria.

The catch is that, over time, successful growing companies are included into the index and unsuccessful ones get thrown out. So of course the index looks good! It only shows the winners… the losers fall by the wayside.

Imagine car companies discarding broken down vehicles from their product testing results. There’d be outrage. But index investing proponents are doing the same thing.

This inconvenient truth about indices is known as Survivorship Bias in academic circles. It’s well studied and understood. A recent study shows just how flawed index investing is.

Professor Hendrik Bessembinder put together a database of almost 26,000 US stocks from 1926 to 2015. Less than 4% of those shares provided the real gains in the index. Only 86 companies were responsible for half of the returns over the nine decades.

In other words, very few companies made investors money. The rest are rubbish: “Slightly more than four out of every seven stocks do not outperform Treasury bills over their lives,” Bessembinder wrote in his draft. In other words, you’d be better off sticking your money in the safest investment in the world, US bonds.

If you didn’t buy shares in those 86 companies, your attempt to match the index would’ve fallen terribly short. In other words, you still have to buy the right stocks at the right time, just to match the index.

Last but not least, do you find it odd that Buffett, the world’s best example of value investing, is telling you not to bother competing with him? Just stick to the index while Buffett buys the real winners on the cheap…

A proper solution

The real solution to investing is the one which Buffett employs himself. Not for his shareholders, mind you. But for his pride and joy – Berkshire Hathaway. The holding company’s holdings are overwhelmingly dividend paying stocks.

This makes simple sense. Investing for retirement shouldn’t be a gamble on capital gains. If you were a business owner wanting to retire, you’d retire off the business’ dividends, not dealing in its shares. Stocks are just ways of owning parts of businesses. Casinos are for gambling.

The beauty of the stock market is that you can own a diversified selection of businesses. But unless they pay you to own them, you’re just punting at a casino without free drinks.

The big question is which dividend stocks to buy? And how do you make sure they’re properly diversified?

Stephen Bland has the answers.

Until tomorrow,

Nickolai Hubble

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Economics