Last week I told you the one place former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan highlighted as the site of the next major financial crisis: Europe.

I want to add some meat to the bones of that prediction. I’ll explain just how severe the threat is, and what you need to do about it right away.

Investors’ Pick: Guide to Understanding the Price of Gold

In particular I want to show you how the financial problems building in the European banking system will morph into a political crisis that could strike a mortal blow to the entire European project. If these problems continue to escalate… there won’t be a Europe for Britain to negotiate with in two years’ time!

As these problems escalate, they could trigger an almost unthinkable event in our own, fatally flawed financial system. If you have savings in a UK bank, own your own property and are financially responsible for your family… let me show you what could happen.

The end of Europe Fair Warning: you might not like what you read in this report. Discover why Europe is doomed politically and financially and what this means for your money. Capital & Conflict is published by Southbank Investment Research Limited. |

Will the EU collapse?

First off, our meeting with Greenspan was private. There were no representatives of the mainstream press (most of whom were down the road from us in Washington, preparing for Donald Trump’s inauguration). With that in mind it’s worth us looking at precisely what he said concerning Europe since… well… you won’t find it anywhere else but here.

Here’s what Greenspan said, with added emphasis from me.

There’s one thing that bothers me considerably, which nobody makes any mention of. There is in the European Central Bank a mechanism as it exists of necessity where the European Central Bank is made up of the central banks of the European, euro area and there’s a thing called TARGET2, do you know what TARGET2 is?

TARGET2 at this particular stage is turning out to be an extraordinary large transfer from Bundesbank to essentially Italy and Spain, and most recently the European central bank. That means the Bundesbank is lending money to the European central bank and the question is – it’s big numbers. We’re talking 7, 800 billion euro.

This can’t go on indefinitely because at some point somebody’s going to have the courage to move Greece out. Greece is in the ECB by accident. They came in under false pretenses and the government, immediately following the government that got Greece fraudulently into the ECB, said the numbers were all wrong and if they were actually the numbers used they would not have been in, but nonetheless they let them stay. That was a terrible mistake. The Greek personal savings rate right now is -20%. You cannot run an economy at -20% savings rate.

Something is going to happen there. My view is it’s either going to be Greece – it conceivably could be Italy. The funny part of it is that the second largest contributor to the net flow in lending to Spain and Italy is Luxembourg. They’ve got some steel and they’ve got a few other things and they’ve got some banks, but it is extraordinary what is going on in this system while the total assets of [the] European Central Bank continue to go straight up. What would happen if there was a default of the euro?

In the United States, if there were a default on the dollar the US treasury could always [step in]. For example, if the federal reserve went into default the US treasury would bail it out but what do [European banks do?] There is no comparable vehicle to help the system.

I’m very worried. Mario Draghi, whom I know and he’s a very good guy, is just talking like we’ll do whatever is required. Well at some point somebody’s going to say, “I don’t want to accept euros.”

A detailed analysis of the TARGET2 system is beyond the remit of today’s letter. Look out for it later in the week.

But let’s dig into what else Greenspan said. There’s a whole sordid history of central and commercial banking subterfuge hidden between the lines. Take, for instance, the fact that Greenspan is direct about the fact Greece should never have been allowed into the euro to begin with. He even uses the word “fraudulent” to describe its admission.

But then, it’s ironic that he outlines what a good guy ECB chief Mario Draghi is in the very next breath. Why?

Because it was Goldman Sachs that helped Greece cook its books in such a way that it could enter the euro to begin with. The head of the GS international division for large parts of that process was… who?

You guessed it! Mario Draghi!

Never underestimate the ability of the Deep State and the global financial establishment to look after one another. The risks of cutting anyone loose or showing any genuine critical thinking about their actions would be highly dangerous to the system. Whether Draghi is a good guy or not is beside the point. But we certainly can’t take Greenspan’s word for it.

How Europe’s financial crises become political nightmares

It is worth considering why Greenspan is so concerned though. He highlights Greece and Italy as potential flashpoints in the next European crisis. Clearly Greenspan believes the endgame is a crisis in which the ECB becomes powerless due to the fact that people won’t accept euros any longer.

That crisis would have to be both financial and political in nature in order for something that drastic to happen.

How precisely would it blow up?

We’d need to see a renewed flare up in the “periphery” nations. Except this time the contagion wouldn’t just be financial, but political too – we’d likely see not just a spike in bond yields, but in support at the polls for anti-establishment, anti-euro parties.

2017 certainly has the potential to be the moment that happens. Perhaps it’ll be the endgame for the European project.

In short, Europe has always been a political movement. It’s held together by political commitment. Logic dictates it’ll take a political disaster for it to end. But financial forces will create the conditions to make it possible.

Exactly what could that bring that about? Well, we’ve covered Greece. It shouldn’t even be a part of the eurozone. But then, it’s already knee-deep in a depression that’s bleeding the nation white. It hasn’t cracked yet.

But what of Italy? What could put the Italians in such a position that it could bring the entire system down?

That’s something we’ve been covering in detail for 12 months now. Tim Price, in particular, has been tracking the problem that’s come to be known as “Le Sofferenze”. Here’s how Tim put it in a recently published warning on the fate of the European project.

“Le Sofferenze” is what the Italians are calling their banks’ bad loans.

It means “the suffering”.

These non-performing loans are now so big they are stifling any hope of a banking recovery.

It all comes down to the country’s failing economy, which is still 8% smaller than it was BEFORE the 2008 financial crisis.

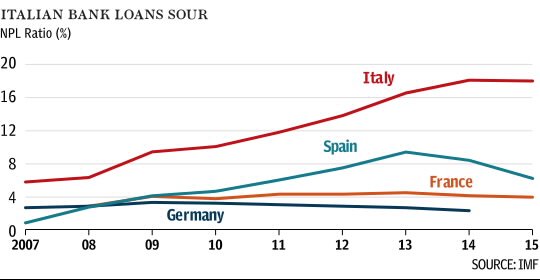

The chart below reveals the scale of the problem. Le Sofferenze now account for 18% of all loans.

To put that in context, Britain’s banks’ “bad loans” amount to less than 1.5% of their total. The global average is 4.3%.

And the problem is getting worse at a frightening speed: in the last five years, the sum of non-performing loans has increased 85%. The total now stands at €360 billion.

Let me repeat that: Italian banks have taken on 85% more “bad debt” in the last five years alone.

They do not have capital reserves to cover anywhere near that amount should they default.

Now, you only need look to the last crisis to understand how devastating non-performing loans can be to the global economy.

The 2008 recession was triggered by the build-up of bad loans in the US housing sector.

But the percentage of bad loans made by US banks in 2008 was just 5%. The bad loans made by Italian banks are currently more than three times that level.

So imagine the financial chaos, social unrest and negative impact of the last crisis all over again – and perhaps even worse.

Then you have weakness across the rest of the eurozone. Including inside systemically important banks right at the heart of the European project. As Tim puts it:

In June, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) labelled Deutsche Bank “the most important contributor to systemic risks among the global banks”.

That’s a diplomatic way of saying: if Deutsche Bank goes down, the global financial system might be severely impacted.

It’s not hard to see why: Deutsche has derivatives contracts (obligations to buy or sell assets) worth an estimated €46 trillion. According to the Bank for International Settlements, that’s approximately 12% of derivatives outstanding worldwide. The sum is also roughly 14 times more than Germany’s GDP.

Deutsche has been in disarray for years now.

Restructuring its business model and building up capital to deal with litigation after years of malpractice has proven highly damaging to the bank.

In September, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) proposed that the bank should pay a $14 billion fine – to settle claims Deutsche mis-sold mortgage-backed securities before the financial crisis. While this figure is not set in stone, the bank only has $5 billion to cover it. Should it fail to persuade the DOJ to reduce the fine, it will be required to raise more capital urgently.

Deutsche Bank is in such a bad state, billionaire fund manager George Soros actually made a €100 million bet against the bank right after Britain’s EU referendum, predicting it would crash.

Deutsche Bank has made a lot of loans to the Italian banking system, too. That’s part of what’s weighing it down. Like I said, they’re joined at the hip. I’ll come to Italy shortly, but the long and short of it is – it’s not likely to get all of that money back.

There are problems elsewhere, too.

France:

Using the US stress test system, French banks BNP Paribas and Societe Generale – two of the six biggest in Europe – were found to have capital shortfalls (money required to survive a future crisis) of €10 and €13 billion respectively.

Only Deutsche Bank requires more (€19 billion). Another study concludes that France requires more money – in absolute and relative terms – than any other country to meet these requirements.

Spain:

In May, Spain’s Banco Popular saw its share price drop 25% in one morning after it admitted it needed to raise €2.5 billion – just one month after claiming it had “one of the best” savings reserves in Europe.

Remember the thesis we’re testing. The financial problems within the European banking system are going to morph into political problems that will pull the European project apart in 2017.

Bad debts, low growth, capital shortfalls, a business model slammed by negative rates… they’re the gunpowder.

What they need is a spark.

The downfall of the European Union

And that’s where politics comes in.

I believe I can show you, down to five dates you need to mark on your calendar, precisely when the whole thing will go up in flames.

We’ve seen recently that problems created by economists and financiers have a way of morphing into mortal threats to the political establishment. Just look at Brexit.

Take much of the mainstream press at its word, and the only narrative that explains last June’s vote involves immigration. I think that’s wrong. The idea that people who voted for Brexit did so because they’re worried about immigrants threatening their jobs just doesn’t stack up.

Consider the numbers. 61% of over 65s voted to leave the European Union. 56% of people in the 50-64 bracket also voted to leave (according to a YouGov poll). These are people who are either retired or about to retire. Fear of people “taking their jobs” isn’t really a logical motivating factor.

A far more logical explanation for people in those demographics voting against the establishment in large numbers would be financial. As global strategist Jim Walker put it last week at our closed-door roundtable discussion with Alan Greenspan, these are people who have been hardest hit by low interest rates and quantitative easing (QE). Those policies have seen traditional sources of investment income dry up and annuity rates collapse.

Which is all a rather long-winded way of proving my point: financial crises can morph very quickly into political crises capable of overturning the established order.

Which, of course, brings us back to the main topic: Europe. Specifically, how financial problems within the European banking system create the perfect backdrop for a political crisis that could threaten the entire European political elite.

The EU Crisis Calendar

There are plenty of financial problems to contend with in Europe. A fundamentally unsound monetary-but-non-fiscal union. Bad debts within the banking system in Italy. Systemically important banks in Germany suffering. Capital shortfalls in French banks. Low growth all round. Negative rates on savings just to make doubly sure the saving populace know they’re being utterly shafted.

Well, get ready. Because 2017 will be the year those problems manifest themselves at the polls.

That’s because, this year more than any other, there are several clear-cut opportunities for the people of Europe to send a message – or a shockwave – through the heart of the European political establishment.

As former US Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers put it, “If [Marine] Le Pen comes to power in France, if an anti-euro party comes to power in Italy, this could be the beginning of the end of Europe and the eurozone”.

Our own Tim Price put it more bluntly in a recent letter on the topic:

The eurozone is on the precipice of a political collapse.

A series of elections will be held in 2017, with many to be fought on lines of “for” and “against” membership of the euro. For the first time since its inception in 1957, the European Union cannot afford to take its future for granted.

France – 23 April: the far-right Front National party is the second favourite to win the presidential election and is avowedly anti-EU. Even if it doesn’t win, it is still pulling France in an increasingly anti-EU direction.

Germany – by October: Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party has been losing seats to the anti-EU Alternative For Germany (AfD). A Merkel defeat would be the biggest possible blow to the EU’s future. Germany is the continent’s biggest economy.

Italy – by April 2018: general election after pro-EU prime minister Matteo Renzi was comprehensively defeated on 4 December 2016 in a constitutional referendum. Italy’s three opposition parties are in favour of leaving the euro, which they believe is preventing the country’s economy from growing.

Italy is perhaps the country with the biggest financial problems

Its banking system is suffering with an eye-watering number of non-performing loans. It had to bail out its oldest bank, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, just before Christmas. And on top of that, the entire nation has already experienced a decade of virtually zero growth (on top of virtually zero interest rates!).

Tim quotes economist Roger Bootle, who agrees with that assessment. Here’s what Bootle had to say on an imminent Italian departure.

“My view is that Italy is more likely to leave the euro within the next year or two.

“The boost that this would give to Italian competitiveness would see Italian GDP recover and this would prompt other southern countries to leave. Before long, the euro would be in tatters.

“Could the EU itself survive the collapse of its greatest project, along with the consequent recriminations and financial wranglings between Germany and the southern members? I doubt it.”

Those three major threats to the European political establishment – votes in France, Germany and Italy (potentially) – aren’t the only opportunities for anti-establishment movements to take root in Europe. But they’re certainly the biggest.

Any major change to the political landscape in those “core” nations would vaporise the glue that holds the European project together. It would only take one unexpected negative result (from the perspective of the mainstream media and the political elite) to make 2017 the year of europocalypse.

But it’s not just a case of those three nations. There are more votes on the horizon in the “periphery” nations. Tim explains:

But the potential dangers do not end with France, Germany and Italy. Other eurozone members holding elections soon include:

Netherlands – 15 March: Geert Wilders has vowed to withdraw the Netherlands from the EU should his surging far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) win.

Hungary – by Spring 2018: the popular current prime minister Viktor Orban has incurred the wrath of the EU by erecting wire borders around the country – in defiance of the EU, which he openly disparages.

The economic failure of the euro is now starting to manifest itself politically. As deputy assistant secretary of the US Treasury, Dr Christopher Smart led the US response to the European debt crisis. In a paper for the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, published in January 2017, he writes,

“The European Project looks in trouble once again. Mounting political extremism, feeble growth and the loss of its second largest economy shape a convincing case that the integration of Europe’s political and economic institutions has failed to deliver. Sharp and unexpected political developments—a populist election victory or a fresh immigration crisis—may well trigger events that lead to miscalculation and collapse.”

So what do you do, as a British saver and investor, to keep your wealth safe during such a time?

My first piece of advice is: don’t assume this won’t affect Britain – or you personally.

Let’s take the national level first. Britain is about to start negotiating on our exit from the European Union. The internal politics of the people we’re negotiating with matter greatly in those talks.

Now is the time to make sure you and your family are protected from any fallout. Like it or not, the EU is still our biggest trading partner. And Britain is in no position to be complacent economically – a subject I explain in full here.

The scale of our public debt is now unmanageable. Brexit or no Brexit, a day of reckoning is approaching for British citizens. This is how I suggest you prepare.

Best,

Nick O’Connor

Publisher, Capital & Conflict

Related Articles:

Category: The End of Europe