Sterling was once the backbone of the British Empire, the go-to currency of the globe, the solid foundation on which international free trade was built.

Now, well, it’s bit of a dog.

In fact, in 2016 it’s been a proper dog.

Today we consider a question to which nobody knows the answer, even if they say they do: what’s next for the pound?

Wherever stockmarkets go, sterling follows

First, an observation on how quickly things change.

In my New Year predictions piece, written in the first week of January, I said that that the pound would slip against the dollar, below the 2015 lows of $1.45, and suggested “we might even flirt with $1.42 and lower”.

January is not even over. We’ve already been there and done that. Last week, sterling touched $1.40.

The pound is heavily correlated to the stockmarket – in particular, the S&P 500. When the S&P falls, so does sterling – and vice versa. I’ve not done any detailed research into why this is, and, to be blunt, as an investor, the ‘why’ is not that important.

But the obvious explanation is that the UK economy is heavily geared to finance, so, when stockmarkets fall, so does the pound. In short, sterling has tanked because stockmarkets have tanked. When they rally, so will sterling.

I can blather on about tax revenue not matching government spending, about current account deficits and unpayable national debt. Or about the falling oil price affecting North Sea output. Or about our economy being over-leveraged towards housing. Or the forthcoming Brexit vote and the volatility that creates.

There are any number of reasons to be short the UK’s money. But the simple reality is, whither stockmarkets, thither sterling, and vice versa.

Is this more than a typical bear market?

I have to stress, my initial reaction to falling stockmarkets was that this is a long-overdue cyclical bear market.

I’ve been doing rather well on the short side (if you’ve been reading my stuff over the last few months, you’ll remember that I’ve made various recommendations on the short side – Netflix (Nasdaq: NFLX) and Skechers (NYSE: SKX) most notably).

And last week, feeling rather pleased with myself, I closed most of them out, thinking we’d now reached oversold levels and could expect a rally into February and March, before the final leg down. Deep down, I guess I’ve been assuming that zero interest-rate policies, quantitative easing (QE) and loose money would keep asset prices propped up and mitigate any bear market that got too severe.

But this selling is relentless, so I’m now starting to wonder if it’s something a bit more serious. The oil price crash is indicating that it is.

Anyway, following my “keep it simple” approach of last September, the bottom line is that this is a bear market. We should position ourselves accordingly – in cash and on the short side – and let the bear market do what it has to do, be it natural correction or something more severe.

So, back to sterling. In the intermediate term, whether it’s against the euro, the yen or the dollar, the trend is down. Simple. The pound is in a bear market.

In the very short term, it’s probably a little bit oversold, and is due a retrace – which we now seem to be seeing.

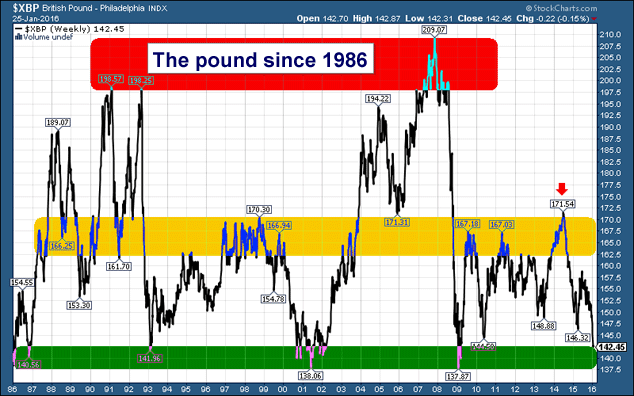

And in the longer term (at least against the dollar), we’re starting to reach extreme levels of weakness, where sterling has historically found support. Here’s my long-term chart of the pound since 1986:

The red band, from (using round numbers) $2.00 to $2.10, is about as strong as the pound gets. We got there in the early 1990s and at the peak of the global debt bubble in 2007. As the saying goes, nobody gets poor selling the pound at two dollars.

The amber zone marks the middle of the range. Support in times of strength (2003-2007) and resistance during periods of weakness (2008 till today).

The green zone is where our focus must be now. Sterling seems to visit this area once a decade, or thereabouts. After the European Exchange-Rate Mechanism debacle in 1993, the dotcom bubble in 2001, and the global financial crisis in 2008-2009.

And last week.

Could we be looking at parity with the US dollar?

Those first three visits were extreme times. This crisis barely feels like it’s got going. That points to lower prices. Indeed, far greater heads than mine are calling for parity with the US dollar. Phew, that would be quite something.

We saw something akin to that in 1985 at the height of Margaret Thatcher’s unpopularity, during the miners’ strike. What drove it then was probably, as my colleague Charlie Morris notes, a US dollar story – the dollar’s enormous strength between 1980 and 1985, which ended with the Plaza Accord to depreciate the currency. In terms of price history, parity (or close to it) was an aberration, not seen ever before or since.

The price history of the last 30 years says that sterling will not go below the green band. So, for now, I’ll stick with that, and argue that sterling will not go below $1.37 in this bear market (on a weekly closing basis). The likelihood is that support will be found somewhere between $1.37 and $1.40.

But, as noted, this bear market does not feel like it’s over, so I would venture that the low will be closer to $1.37 than $1.40.

Below that green band, however, and parity comes back into play. A year ago, I would have dismissed talk of parity as ridiculous. But this year has already shown how quickly perspectives can change. And, again, this crisis feels young. It doesn’t even have a name yet. It’s almost happening by stealth.

A fund manager suggested to me the other day that this might be “the one”, the crisis that’s been coming for so long but keeps getting put off. Who knows, maybe it is. (I’m not sure I believe in such things, by the way.)

But I make the observation that the selling is relentless. If this crisis really gets going, then the outlook for sterling is ugly.

The best way to play all this is, simply, to hold other currencies, assets denominated in foreign currency and, of course, gold.

Category: Market updates