On the old pilgrims’ road to Rome lies a public square. Off the square is an imposing gothic building that has stood since before the Renaissance, fronted with a huge wooden door. Behind that door lie the headquarters of the oldest bank in the world. Inside the bank there are cabinets stuffed with thousands of old documents…

And what’s written on those documents could soon plunge the entire banking system into crisis.

In a world where the vast majority of financial data is digitised, where you can take out a loan, trade shares or manage your finances online, that might sound like a strange idea. Stacks and stacks of real documents, filed away for years – maybe even decades – inside an old and venerable bank, containing information of vital importance to the future of the financial system.

It emerged yesterday that in the back offices of Monte dei Paschi di Siena, the oldest bank in the world, there’s a huge operation underway to sort through stacks of documents that contain information about loans made long ago, many of which may have gone bad and are now a threat to the bank.

I visited Siena, and the headquarters of Monte dei Paschi, over the summer. There are worse places in the world to work. At least, once the working day is over and you’re out enjoying the pleasant public squares, there is good wine and food and incredible architecture. Who knows what it’s like in the day as you sort through thousands of old documents, painstakingly working through a financial nightmare.

But it’s a true story

Reuters interviewed some of the people involved yesterday. As it put it:

Dozens of analysts have been toiling in back offices of the nation’s third-largest lender, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, in the first stage of a campaign to sell or recover much of Italy’s 360 billion euros ($395 billion) worth of problem loans.

The analysts, engineers from a loan data firm, have worked for almost a year with the bank’s officials to comb through aging files, copies of which are kept in binders tied together with string and stacked in cupboards, in order to help prepare a 28 billion euro bad loan sale.

“Ours is a painstaking job,” said Luca Mazzoni, chief executive of Protos, which has been hired by Monte dei Paschi.

“Documents associated with a single loan can take up an entire cupboard. In one case I remember half a room filled with papers related to just one loan.”

The loans themselves may be something of a non-digital anachronism. But shares in Monte dei Paschi aren’t. They’re thoroughly digitised. And they’re taking a hammering. Yesterday shares plunged 23% and had to be temporarily suspended. The bank is in the process of trying to push through a “turnaround plan” to save itself.

The problem is, the situation the Italian banks find themselves in isn’t the kind of thing that can be turned around quickly. Or possibly at all. And that’s important for you, because if contagion in the banking system spreads we could all be in for a hell of a winter.

Bad debts, bad banks, bad news

Monte dei Paschi isn’t considered a systemically important bank – ie, a bank that would immediately put the whole system into trouble were it to fail. It’s more symbolically important. But as the oldest bank in the world, it’s a heck of a symbol of a financial system rapidly going sour.

The reason for that is those bad loans. At Monte dei Paschi it turns out many of those loans were made long ago, written up on paper and stored at the bank and are now going bad.

But ultimately it doesn’t matter if the loans are written down on paper or digitised. If they’re bad, they’re bad. And if enough of them are bad and can’t be paid back, this sucker is going down (as George W Bush once said of the US financial system).

Bad loans across the Italian financial system have been on the rise for years. Keep in mind that bad loans are all part and parcel of the banking industry. If your job is to loan people money then it stands to reason that some of those loans will go bad: some of the people you lent money to won’t be able to pay it back.

That’s normal. So you keep a certain amount of capital in reserve to protect you when some loans go bad. You do your best to keep bad loans down by understanding who you’re lending to and what they’re going to do with the money.

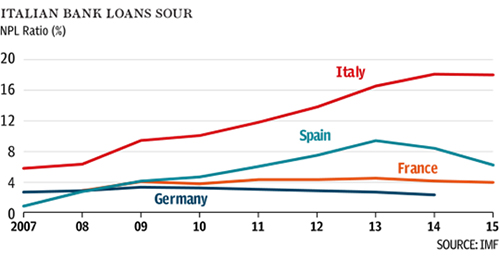

The average number of bad loans for a bank in the modern world is 4.3%. For every 1,000 loans you write, 43 will go bad.

In Britain, the number is even lower today: just 1.5%.

In Italy? It’s 18%!

That’s right. There are four times more bad loans sitting on the books of Italian banks than the global average. Four times! And the number is growing; presumably as analysts work through the back offices of banks like Monte dei Paschi, discovering more horrors within.

How do you end up in that kind of fix? Two ways. Either you loaned money to people who couldn’t pay it back… or something has happened in the economy that suddenly puts large numbers of people into difficulty. At a guess, I’d say it’s probably a bit of both in Italy.

Either way, this chart tells the story. You can see that non-performing loans in Italy have spiked since the financial crisis, far more so than across Europe.

Mario’s banking dilemma

Mario’s banking dilemma

There’s an interesting little side story unfolding here though – a human story that adds a layer of drama and unpredictability.

In 2008 the Italian banks chose to “roll over” their bad loans. That made sense. It was an extraordinary time. Rolling your debts over means giving people more time to find a new job or do whatever it takes to start servicing your debts again. It worked in a way – it delayed the pain. But the economy hasn’t recovered enough to salvage many of those loans. They’re still bad. And now they threaten to push the Italian banks to the edge.

That’s where things get interesting on a more human level. Who was the governor of the Bank of Italy in the financial crisis?

Answer: Mario Draghi – the man who is now responsible for the entire European banking system.

Draghi will still have long-standing friends and connections within the Italian banks. He has a personal interest in the system. But the problem is, these days you can’t go handing out bailouts to your mates like it’s 2008. European Central Bank rules state that creditors, bondholders and shareholders in the banks have to be “bailed in” before any taxpayer money can be injected.

That’s bad news for Italian savers, who are unusually large holders of Italian banking bonds. And it puts Draghi in a bind: bend the rules to save your old mates and risk the wrath of the Germans… or follow the rules you devised and potentially ruin thousands of ordinary savers and pensioners in your home country?

Of course, there is no “home country” in Europe. It’s all one big happy federalist family! They’ll all look after one another. National allegiances won’t come in to it at all.

Ahem.

Today’s issue is dedicated to “le sofferenze”

I shouldn’t joke. But when the situation is dire, sometimes a little levity is all we have to keep the darkness away. That said, we should remember that there’s a very real threat here.

To Italians, the threat is constant, and right on their doorstep. For the rest of Europe – and the world – the threat might feel further away, but it is no less significant. A banking crisis in Europe could have ramifications for everyone. And that means you need to understand how it’d affect you, and have a plan for what to do if things go sideways.

To do that I recommend you read a report that award-winning defensive investor Tim Price has put together. It won’t make for pleasant reading. But it’s not a pleasant situation. As Tim says, the Italians are now calling their bad loans “le sofferenze” – the suffering.

So I can’t promise you a happy read. But reading Tim’s report will give you the understanding and clarity you need to see what’s coming and what you need to do about it. That’s an extremely valuable purpose.

You can read Tim’s report here right now.

It’ll only take ten or 15 minutes to read carefully. But it’s worth your time. The clock is ticking. Who knows what other terrors lurk behind the doors of the Italian banks?

Until tomorrow,

Nick O’Connor

Associate Publisher, Capital & Conflict

Category: Central Banks