In a credit bubble, mistakes are inevitably made. Credit gets mis-allocated. Bad investment decisions are made. Risks are misread. You never get a new cycle of genuine growth until the losses are realised and the bad loans are liquidated. You recognise your mistakes, take your medicine, and move on with a cleaner, healthier, less debt-burdened balance sheet.

Of course one likes to take medicine like that. And by lowering interest rates and instituting asset purchase programs, central banks have prolonged the agony and delayed the recovery by preventing the recession we need to have. Now we won’t get a recession. We’ll get a depression.

If it doesn’t begin in the sovereign bond market (an issue I discussed earlier this week) it could be the corporate bond market. The number of ‘least creditworthy’ companies is near an all-time high, according to ratings agency Moody’s. The agency says there are 274 that are ‘six notches’ into junk territory. The all-time high number was 291 in April of 2009.

The energy sector accounts for 31% of the junk ratings. You’d expect that with the crashing oil price. But retail isn’t so flash either. And really, it makes sense that it would all begin with energy. The shale-boom in the US was financed with borrowed money. The energy bubble was just another manifestation of the credit bubble.

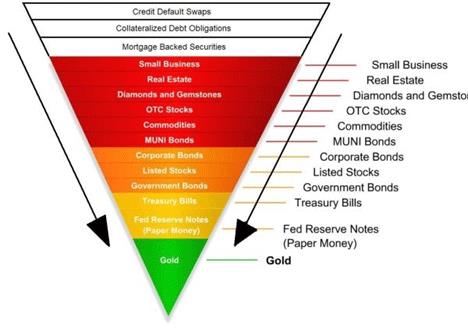

Looking at cash, oil, corporate bonds, sovereign bonds, and stocks, I was reminded of John Exter’s obscure but useful ‘inverse liquidity pyramid.’ I’m not sure Exter ever called it that, by the way. But I called it that when I wrote about it at the end of 2013. First, take a look at modern version of the pyramid below.

Next week I’ll republish some of what I wrote about Exter in 2012. For today, the important point is that in a deflationary crisis, Exter predicted that investors would move ‘down’ the pyramid into higher-quality more liquid assets. The bursting of a credit bubble would see capital flee riskier, debt-based assets into more tangible and liquid assets.

Keep in mind that when Exter wrote about the pyramid in the 1970s, the government bond market was smaller. Today, with the explosion in government debt, the sovereign bond market is enormous. There’s some doubt—at least in my mind—about whether government bonds are ‘high quality.’ They’re certainly liquid, at least for now.

You can see the problem, though. The closer you get to the bottom of the pyramid, the fewer options you have. You can be in cash (legal tender backed by nothing) or short-term government bills and notes. But those are both obligations, or promises to pay. The promise is only as good as the government or central bank making it.

My argument in 2012—and it would be the same today—is that high quality blue chip stocks with ample liquidity might be ‘safer’ than what Exter thought it the 1970s. Of course nothing in the stock market is ever ‘safe.’ The stock market is not a savings account.

I’ve shared the idea with my colleagues here (Charlie Morris, Tim Price, and Alex Williams). The jury is still out. I’ll have the verdict on Monday.

Category: Market updates