I was caught in the crossfire of the currency wars last month.

I sold some shares in a German property fund. In the time between agreeing a price and the money being sent (there were delays for various reasons), the Swiss National Bank decided to unpeg the franc from the euro.

Then, the Coalition of the Radical Left – known to you and me as Syriza – won an election in Greece.

As the euro tanked, my jolly sensible, low-geared investment lost 8% or so of its value in the space of less than three weeks. It riled.

Pity the importer or exporter – someone working in the real economy, rather than the financial – who gets caught in the crossfire of these wars every day.

With the world’s central bankers showing no signs of declaring a ceasefire, in today’s Money Morning I want to consider the outlook for one of the main players – the euro – against the US dollar and the pound.

The US has enjoyed a massive transfer of wealth

People wonder when the bond vigilantes, so notorious in the 1970s, are going to return.

I suggest that that they are already back – hard at work in the forex markets.

Let’s start with the euro against the dollar. It’s amazing to think that in the heady days of 2008 the euro stood at $1.60. The current price is $1.11. The net worth of the entire continent has been devalued by 30%. It’s quite something when you think about it like that. Even last summer it was trading at $1.40.

When you also factor in the considerable outperformance of American stockmarkets relative to their European counterparts, you get an idea of the colossal transfer of wealth that has taken place. The US has grown very rich.

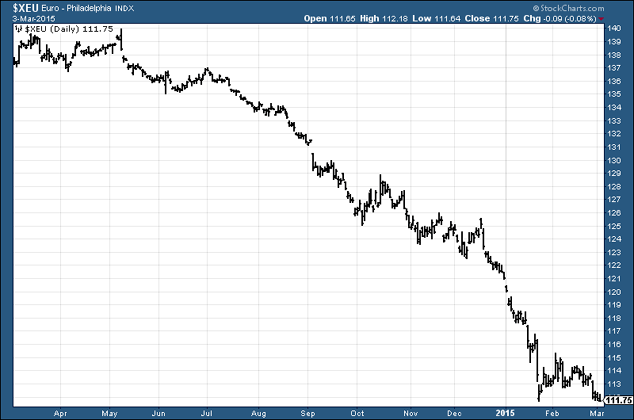

The chart below shows the euro against the dollar over the past 12 months.

It doesn’t take a genius to see the direction of that trend.

However, the euro is very oversold. There does seem to be some kind of battle going on at the $1.11 mark, where a possible double bottom is shaping up. The question is whether we get a rally.

Short-term moves are about as easy to predict as the outcome of a coin toss, of course. But I can’t say I’m bullish. Maybe we’ll bounce to $1.15, but the market is all too aware that there’s a lot of proverbial in the pipeline.

My prediction at the start of the year, with the euro at $1.20, was that we’d get to a low of $1.08. We’re only 3c from that now. There’s more Greek stress in the diary four months from now, and a whole pot of problems brewing in Spain with its general election, and the rise of Podemos.

Then there’s quantitative easing (QE), unconstitutional deficits being run across the continent, debt levels in many cases in excess of 100% of GDP, perceived deflation, social unrest and so on.

It’s all been heavily priced in, of course – but it doesn’t exactly make you bullish.

The pound looks set to rise against the euro

We look next at the pound and the euro. In the currency premiership, the dollar is very much Chelsea. The euro has taken on the role of Leicester City. Sitting in mid-table mediocrity, the Everton or Newcastle of currencies, (a big club, a lot of potential, not really delivering) we have sterling.

The pound has been awful against the dollar, but it’s been a lot better than Leicester City.

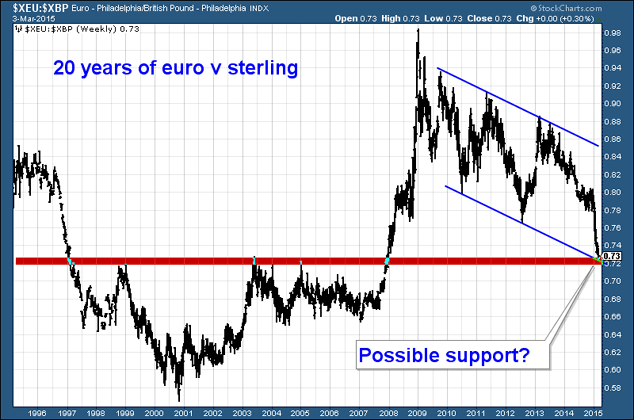

It’s amazing to think that in early 2009, the euro almost reached parity with the pound. Like the euro-dollar, the trend of the euro against sterling is very much down. 2013 saw highs of around 88p, 2014 at 84p. The waterfall has been in 2015, from 79p to below 73p yesterday.

It can go a lot lower.

Here’s a 20-year chart. You can see that in 2000, the price was below 58p!

The red band shows an area of possible support, based on previous support and resistance levels. The blue tramlines define the current trend – and we are at the lower end of the range.

So you could make a simple technical argument that the euro could begin a bear market rally of some kind. Actually, on a risk-reward basis, going long the euro against the pound at 72/73 with a stop below 72p doesn’t look like such a bad bet.

But I’ll let somebody else take on that trade.

Money is a political tool

Money is, of course, issued by governments – and so it is a political tool. In trying to divine the future, you have to consider the decisions that central banks and their political masters are likely to make. Of course, some benefit hugely by the decisions that get made, while others don’t.

Whenever I look at currency fluctuations, I’m always interested in the effect they have on ordinary people trying to get on with their lives.

The wealthy French family that came to London to escape Hollande’s taxes, for example, has done very well. The London house they bought has appreciated, the currency it is valued in has appreciated, and the money they are now being paid in has appreciated. The last five years have turned out rather well, thank you very much. No wonder London is now France’s sixth largest city!

But for the British retired couple, who sold up and retired to France or Spain or Italy, the reverse has happened. The European house they bought has probably fallen in value. The money it is denominated in has fallen in value, while what they left behind has appreciated.

Let’s say they sold a £500,000 home in 2011 and, with the euro at 90p, bought a €550,000 home. Let’s say the British home has appreciated by 15% and the euro home has depreciated by 10%. (I know – I’m using broad brush numbers, and somebody’s going to annihilate me in the comments).

So the euro home is €500,000. With the currency depreciation (90p down to 73p), they can sell that euro home for £365,000. But the UK home they sold is £575,000. That’s quite a substantial loss. Many can’t now afford to buy back the life they left behind.

It’s enough to turn you into a hard money advocate.

And if I was that French family – I’d consider taking profits.

• Dominic Frisby is the author of Life After The State and Bitcoin: the Future of Money.

Category: Market updates